When I ask principals what prevents them from focusing on instructional quality in their school, the number one answer I get is: time. It’s true, time is always a concern for principals, but it is not the only one. I have found that even when principals carve out the time to improve instruction, they are often at a loss for what to do.

That’s a problem because principals matter. School leadership is the second greatest school-related influence on student learning, second only to teacher effectiveness (Leithwood & Riehl, 2003). Without an effective principal in every school, it will be difficult to improve student outcomes and close persistent achievement gaps.

So why do principals struggle to find the right approach to foster instructional excellence? It’s because principal leadership is complex and requires expertise, practice and reflection. As we all know from trying to learn a new skill or change a habit, it is difficult to do without continuous support, a plan, feedback and a way to monitor progress.

At the University of Washington Center for Educational Leadership (CEL), my colleagues and I are working with principal supervisors and principals across the country to form new habits and learn new skills. Over the years we have developed an instructional leadership inquiry cycle tool that helps principal supervisors and principals to collaboratively engage in a continuous process of instructional improvement and analysis.

Let’s take a closer look at this inquiry cycle and see how taking an “inquiry stance” can become a way of working in our schools.

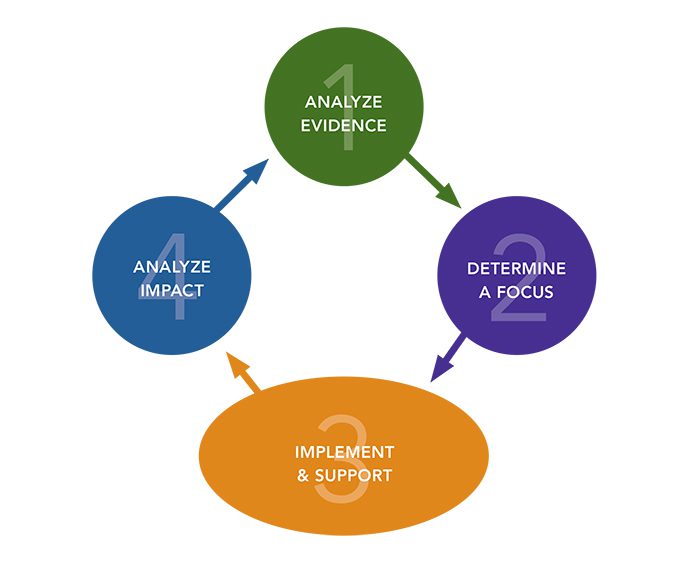

Instructional Leadership Inquiry Cycle

The Instructional Leadership Inquiry Cycle has four phases: analyze evidence, determine a focus, implement and support and analyze impact.

The Instructional Leadership Inquiry Cycle has four phases: analyze evidence, determine a focus, implement and support and analyze impact.

One important piece of advice before you start: don’t try to solve every problem at once. The cycle of inquiry is short term, often completed in three to four months and therefore the student-learning problem and teaching problem are small in scope. The principal area of focus is a specific skill needed to solve the identified teaching and learning challenges.

Step I: Analyze evidence

In the first step, principal supervisors and principals use student test scores, self-assessments, classroom observations and observations of principal practice to identify the most pressing student learning problems and contributing teaching and leading problems of practice.

Questions to help identify these challenges are: What are the learning strengths and challenges of student learning? What are the related instructional strengths and challenges of teaching practice? What type of evidence will be collected to determine the principal’s area of focus? What is the principal area of focus for this cycle of inquiry?

Let’s look at a recent example from our practice. At a 500-student elementary school with declining test scores in mathematics, a large percentage of those identified as English Language Learners (ELL) were not meeting standards in math at the fifth grade level. More specifically, ELLs recently released from ELL programs were struggling with comprehension of mathematics problems and explaining their thinking to others. The principal and his team identified this as the student-learning problem.

The principal supervisor and principal repeatedly observed classroom instruction. They noticed that the four fifth grade teachers were not consistent in giving ELL students opportunities to learn mathematical academic vocabulary or to talk to the teacher or other students. As a result of these observations and discussions with teachers they determined that the key teaching problem of practice was that teachers needed to better teach the vocabulary and the processes for students to engage in effective mathematical discourse.

Step II: Determine a focus

In the above example, the principal completed a self-assessment of the district’s instructional leadership framework and the principal supervisor shared his observations in order to determine a focus. They decided that the area of focus for this cycle of inquiry was for the principal to find out about the resources available for teaching school leaders and staff what mathematical discourse looks and sounds like in a fifth grade math classroom. The principal was also going to learn how to develop systems to hold staff accountable for implementing learned strategies.

One important thing to remember in this phase: be sure to surface the current realities of student learning, teaching and leading practice to project what would count as evidence of success at the close of the cycle.

Step III: Implement & support

Creating an implementation and support plan is the next step in the process. Typically, the principal supervisor and principal set up a series of learning activities together based on the principal’s and teachers’ learning needs to improve student learning in the identified area of need for this cycle.

Critical questions in this phase include: What are the possible actions for a series of learning sessions? How will these sessions improve principal performance?

In our example, the team used the Instructional Leadership Inquiry Cycle to plan a series of four learning visits. It is important to remember that this is a short-term cycle so the learning activities need to be carefully designed to improve principal practice in the identified area of need. Keep in mind that these are learning activities and not steps that the principal is expected to take on his or her own since it was clearly established that this is a task that the principal does not know how to do without additional learning or support.

Coming back to our example, this included working with a math specialist to determine resources, planning professional development activities and observing together in classrooms. During one learning session the principal supervisor modeled a feedback session with a teacher and then provided feedback to the principal when he executed a similar feedback session.

Step IV: Analyze impact

Facing initiative overload, this is the step in the inquiry process principals and their supervisors often skip. This is unfortunate because collecting evidence and analyzing results generated by the actions taken is crucial to building a virtuous cycle of instructional improvement.

Critical questions in this phase include: What was learned about leadership practice and its impact on teacher practice and student learning? What are the implications for the next inquiry cycle?

To share the project results, principals often prepare a written reflection on the changes in student learning and teaching and principal practice. After presenting this to the principal supervisor or colleagues, the team can decide whether or not to continue with the current cycle or begin anew.

Let’s get back to the example we have been following. In this specific case we had a group of principals who were completing their cycle of inquiry at the same time. The principal presented his cycle results to three other principals using a structured protocol. The principal, after obtaining feedback from colleagues, decided that there was enough evidence of improved teaching practice and student learning that he could release the fifth grade team to continue to work with the math coach to further refine their practice. The principal, with input from his principal supervisor, decided to work with the K-2 ELL students and teacher to prepare them better for what they would experience in fifth grade.

The feedback from principals was very positive. Many admitted that at first the process had intimidated them, but after working through it, they shed their earlier reservations and even wanted to continue to work in similar fashion in the future. Some principal supervisors even said that the experience was the best learning they had since taking the position.

Impact on Practice

Getting this process up and running is not easy. But when it grows and takes root it is a powerful force for instructional improvement.

In our wide array of work with principal supervisors, I have seen this many times. In one district a principal supervisor told me that she now has clarity on how to work with principals to help them implement actions to improve teaching practice and student learning. She also recognized that she and the principal do not need to wait for benchmark data or end-of-year assessments to see if student learning is improving. They can see changes in teacher practice and student behavior every day. Many principals comment that the dedicated support and a clear plan helped them to improve in ways they never imagined.

Because school leaders are getting results, they have a greater sense of accomplishment, which – almost everybody tells me – increases their motivation to continue to dedicate time to focus on instructional leadership.